A sermon for Easter Sunday, Year C:

Acts 10:34-43; Psalm 118:1-2, 14-24; 1 Corinthians 15:19-26; John 20:1-18

**

I had some friends in and after college who went to work on political campaigns full-time. It took them weeks to recover from the post-election funk when their candidates lost.

And who can blame them? They put so much of themselves into a cause, into uniting the community around a person they’d come to believe in.

They canvassed. They phone banked. They subsisted entirely on pizza, turkey sandwiches, and whatever was left in the headquarters’ vending machine.

Long days. Late nights. A marathon of sprints. And then finally the polls opened, the people spoke, the votes were counted—and they found out it had all been for naught.

Now imagine what it might have felt like for one of them to be awoken the next morning, post-election hangover just setting in, to find out that a best friend or sibling had died unexpectedly.

That’s gotta be something like the level of distress and trauma experienced by the disciples in the aftermath of the crucifixion. A grassroots religious project and a life-changing intimate fellowship both utterly destroyed by the brutality of an occupier state.

**

One of the great mysteries of the scriptures is why the disciples never recognize the resurrected Christ when he appears to them. Without wanting to rule out any of the more intriguing theories, I kinda think it was pure shock and exhaustion. Like those campaign workers and worse, they were a mess.

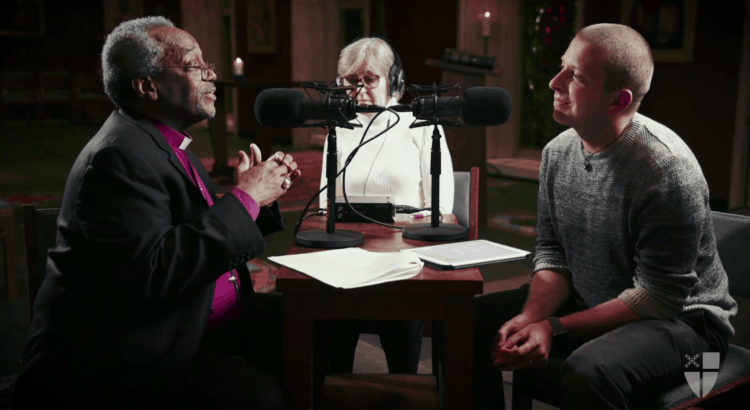

Consider Mary Magdalene. She’s just discovered an empty tomb, run across town to get Peter and John, and then had to put up with their cryptic responses to what she still very sensibly thinks is seriously distressing news.

She came to care for Jesus’s body. But someone has apparently stolen it, and she’s alone, and in the dark, and she can’t do the job she’s come to do, and so she’s probably playing back the scenes of the past few days again, and ooph I know I would crying. And I know none of this would help me with clear vision or critical faculties.

Of all the post-resurrection mistaken identity encounters, this one just has to be the most reasonable. And with Jesus now on the scene, asking her whom she is looking for, notice what cuts through her quite understandable haze of grief and frustration.

“Mary!”

He speaks her name.

And just like that, she is a new creation, like the garden blooming around her. Just like that she becomes the apostle to the apostles.

Not only does she recognize him, she addresses him first and immediately not by his name; and not as Lord or “my Lord and my God,” as Thomas will later exclaim, but as teacher, or perhaps in the Aramaic “my teacher.”

Jesus is the teacher. Mary is the disciple. He calls her by name. And then he sends her off as the first witness of the Resurrected Christ, to tell the other disciples, “I have seen the Lord!”

This brings John’s Gospel full circle, a sly reference to Andrew and Peter’s call to be disciples all the way back in chapter 1. Jesus asks whom they are looking for. They too recognize him as “teacher,” first responding and then passing on his invitation to “come and see.”

**

We’re standing in this church because they did. And especially because she did. They and countless others. Again and again and again and again and again the chain of witness has gone unbroken.

Come and see the one who has changed our lives. Come and meet the community that welcomed me with open arms. Come and learn how loving and serving God and neighbor leads to life in abundance.

“We disciples are witnesses,” says Peter to the gathered friends and family of Cornelius, a Roman army officer. This is in our reading from the Acts of the Apostles, the account of that first generation of witness and the many strange places God led the disciples to share it. In this case, God had heard Cornelius’s prayers and sent a vision that he should invite Peter to come and lead his household into a deeper faith. They would become the first Gentile Christians.

“My friends and I are witnesses,” says Peter, “to the life and death and resurrection of God’s chosen messenger, God’s very Son, who came among us for the work of healing and liberation and who guides our ministry still. Today, that ministry has brought me to your household. Today, you too will become witnesses to power of the Holy Spirit at work in the world. Today you have received this grace as gift; tomorrow, you will share it freely with all who need it.”

**

God’s grace is free gift, offered to all, and today of all days we rejoice and give thanks for its abundance. God’s grace is a free gift, but like our forebears in faith, tomorrow we have work to do.

To be a Christian is to join the current generation of witnesses to the loving, liberating, life-giving work of God. That work has been revealed to us, embodied for us, in Jesus Christ our friend and our savior, and embodied as well in the work of the church, Christ’s imperfect but still desperately needed presence in the world today.

You don’t need much to be a disciple, to be a witness. The call is easy: you’ve heard it. You’re here.

The testimony, the content of our witness, the stuff of our faith, most of us find that a bit more challenging, especially if we’re aware of the baggage so many people carry about God or church. And especially if we carry that baggage ourselves.

Here’s a place you can begin to claim your witness: Find your Mary moment. When has God called you by name?

I don’t mean, “When did you hear Jesus’s literal voice in the early-morning darkness?” Not necessarily. You don’t need to have seen visions of angels.

But your Mary moment might have been an unexpected experience of relief or presence or hope during a particularly desperate hour. Perhaps it came in the aftermath of some campaign or project or period in your life when things had gone off the rails.

Perhaps your Mary moment was an experience or pure joy and exuberance, perhaps an opportunity to serve or be in relationship in a new way. Finding meaningful work. Meeting a future spouse. Meeting your child for the first time, or seeing them again after a long absence. A transcendent encounter with art or music or nature or an old friend or a total stranger.

Perhaps your Mary moment was much more mundane. We can meet the Risen Christ in quite ordinary experiences. Where there is love, where there is freedom, where there is change for the better—God cannot be far away, though we often overlook this, or forget to remember.

Let this joyful Eastertide be for us a time of remembering, and sharing, and being curious. A time of giving thanks. A time for letting God’s healing waters flow over us once again.

We disciples have work to do: for each other, for our neighbors, for our environment, for the world.

Nothing less than Good News recognized and claimed, nothing less than the joy of witness, will empower us to do that work.

We will know the resurrection when we hear Christ call our names.

Image: “Mary Telling the Apostles of the Resurrection” by James McNellis via Flickr (CC BY NC ND 2.0)