A sermon for the Feast of the Presentation (Malachi 3:1-4; Psalm 84; Hebrews 2:14-18; Luke 2:22-40)

Last Saturday, my wife and I were stuck in traffic.

I’d been out of town all week and was feeling stressed and behind on my work. On top of that, we’d just moved, and there were a few more boxes to empty, a few more cables to run and straighten and secure.

And we were heading somewhere we didn’t *have* to go.

The stress for me in the moment led to one of those check-ins that are so important in any relationship. I said I was frustrated about the traffic but restated my commitment to the plan we had made together.

And Kristin said, “Well I’m not in any hurry.”

Now, this is a phrase I probably say more often than she does, and usually truthfully. And yet in this moment, my whole emotional being recoiled at those words.

“How can she possibly say that?!” I thought to myself.

But maybe because I recognized that this was a perfectly reasonable thing to say on a Saturday afternoon, and maybe because I didn’t want to feel any angrier, and maybe because I was literally inching down Nob Hill on Hyde St. with nothing else to do, I sat with this contradiction a bit longer:

I shouldn’t be in any hurry. My God am I in a hurry.

And low and behold, I learned something:

I am always in a hurry in the car. I am technically capable of having a relaxed, ambling sort of attitude on a Saturday afternoon. But not in the car, in gridlock, in the midst of a day that has other things on the agenda.

I feel trapped in those moments. I feel time slipping away. And I’m feeling that even more keenly given that Kristin and I have about 20 Saturdays left before we start sharing them with a newborn.

Those moments in the car gave me some important information about who I am and the challenges that I’m facing, and that we’re facing, right now.

**

In today’s gospel passage from Luke 2, Jesus’s parents bring him to the temple to present him before God. They meet the faithful and eccentric Anna and Simeon, who reveal by grace some essential characteristics of Jesus’s identity and destiny.

The whole passage is about revelation, about uncovering what God sets in motion through this Christ event. Jesus is a sign for Simeon and Anna, a sign for Mary, a sign for all God’s children.

Open your eyes and see this great Light, says Simeon. Our creator reveals our Savior and our path of redemption.

But he goes on to say something I find even more intriguing:

This child is … to be a sign that will be opposed so that the inner thoughts of many will be revealed.

God’s salvation is shining forth, says Simeon. But be prepared to be revealed yourself.

This Holy Child will draw forth the disputations and ruminations and contradictions in the hearts of those who encounter him.

Of course Luke later shows us that this is so. In exchange after exchange, Jesus perceives the deep fears and longings that set his conversation partners on their various paths.

And Jesus represents something to those who encounter him. He is a sign:

- to the crowds, of healing and deliverance;

- to his companions, of purpose and empowerment;

- to the authorities, of a threat to their tenuous grip on control the way they see themselves and their roles before others.

Jesus represents something to those who encounter him, but he is a person, not a principle. He doesn’t mean just one thing.

Jesus transforms us through our encounter with him, a conversation that lasts our whole life long.

**

This season of Epiphany is dedicated to the story of the Light of Christ shining forth for all the world to see.

This Feast of the Presentation offers, in Simeon and Anna, two stirring examples of what difference that illumination might make for those on whom God casts this light.

What difference does Christ make for us, today? What significance do we ascribe to Jesus, son of Mary, Son of God? What inmost thoughts is Christ the Light revealing?

We should start by remembering that the light of Christ shines in the silence of our hearts. Jesus is an invaluable conversation partner as we reckon with our own eccentric and sometimes shameful contradictions. I believe he is within us, loving us, loving us—even when we do not realize it.

As we learn to seek the light—as we learn to listen—our inner thoughts are revealed to us in ways that have the power to heal and to transform. In my example, it went something like this:

Am I really so selfish and distracted that a little Saturday traffic ruins my ability to be an attentive companion? And to my pregnant wife, no less, who just wanted a milkshake and to spend some time with her husband?

To which Jesus responds,

Whoa there. It’s a bit more complicated than that. There’s kind of a lot going on here, right?

Take a deep breath and let me remind you how to be gentle with yourself. If you can remember how to love Kyle, it won’t be long before you’re loving Kristin and the baby and maybe even your fellow drivers congesting Hyde St.

I know you’re capable of that love because I am the source of that love.

Let me love you, Kyle, and I promise the rest will start working itself out.

Did I hear these WORDS, booming through my consciousness in an unmistakable Nazarene accent? Of course not. But it’s in these intense and pivotal moments that we should be confident Jesus is there with us, working out our redemption breath by breath.

Even more important in these tense and frenetic times is that we let Christ reveal and restore what is broken and contradictory in the world around us.

The Light shines and brings the contours of society into sharp, sometimes devastating relief. Jesus offers a moral clarity that tests the way we treat the vulnerable, the way we treat the stranger, the way we treat the planet.

We write “All men, all people, are created equal.” Jesus sees a different reality in how we live this law.

We speak, “Give us your tired, your poor.” Jesus sees a different reality, one he finds familiar, yet all the more incomprehensible in our age of plenty.

Yes, the Light reveals us. The Light shows the biases and brokenness of our life together. The Light shows us lacking.

It can also catalyze the change we so desperately need, giving us energy and direction.

This child is destined for the falling of many, Simeon said. But also for the rising.

Jesus is a sign of love not just for religious insiders, not just for citizens, not just for homeowners, not just for the morally pristine, not just for human beings.

The Light of Christ shines all around us, showing us the way to live as the people of God, amid all of God’s creation.

A sign of love. A promise of love. A way of Love.

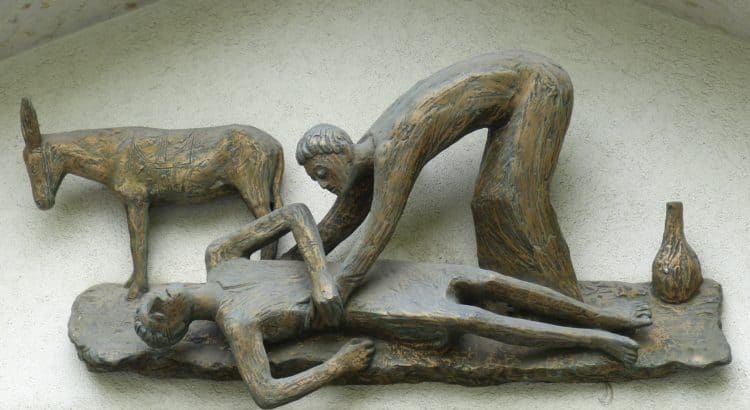

Image credit: “Christ the Light Oakland 17” by joevare via Flickr (CC BY ND 2.0)