A sermon for the fifth Sunday after Pentecost, Year C (Proper 10: Amos 7:7-17; Psalm 82; Colossians 1:1-14; Luke 10:25-37)

“Go and do likewise” was the informal slogan of a wonderful organization with whom I served a January term field placement my first year of seminary.

Samaritan Ministry of Greater Washington started in the basement of a DC church committed to innovative worship, deep relationship, and responsive, mutual presence in their neighborhood.

As such, the organization and its programs evolved into a space where people who are homeless or otherwise marginalized can be seen and welcomed—as opposed to being ignored or chased away. Participants receive support and access to resources as they choose and pursue their *own* goals for improving their lives—as opposed to having goals chosen or work done *for them* by people with the power to set requirements and to claim to know what’s best.

My hosts knew I was unlikely to stay involved after I’d worked my last shift and written my final reflection paper. I handled tasks commensurate with that level of commitment, mostly working the phones during a campaign to mobilize the organization’s supporters for an upcoming auction gala fundraiser.

The most memorable experience of my time there was actually writing the little bits of copy that would be read by the announcer to describe each donated auction item.

“Render unto a friend or loved one this collection of bronze and silver coinage from fourth century Rome.” That kind of thing. I’m pretty sure there were some puns on the different emperors’ names, and like the secrets of the emperors themselves, these puns are thankfully lost to history.

At first I thought it was strange to be a priest-in-training basically doing Price Is Right shtick when he was supposed to be “helping people.”

It turns out the main point of these placements was for us to realize for ourselves that the various roles my classmates and I were preparing for were not significantly different from the discipleship we knew: seldom glamorous, mostly about showing up, utterly unheroic.

With the benefit of hindsight, I suspect even the folks who worked directly with clients at this organization would describe their work in the same way.

**

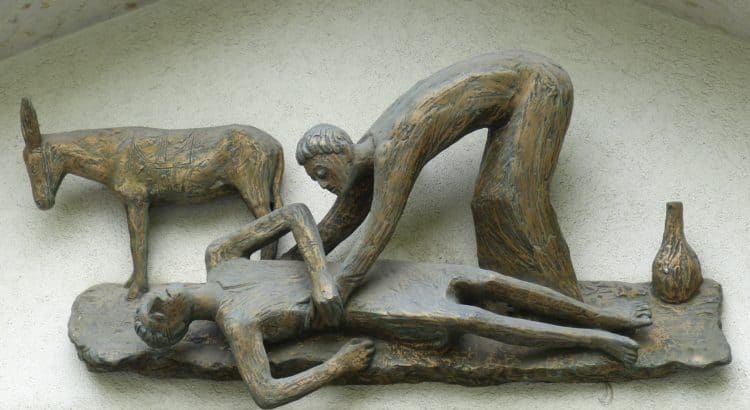

“Go and do likewise.” Those deceptively simple words at the end of the parable of the Good Samaritan feel like the most challenging Jesus ever spoke. Some commentators believe the sky-high moral standard is part of the point.

They argue this parable is an opportunity for Jesus to aud[ay]ciously point out that a nondescript member of a reviled social group could be a more faithful follower of the laws of Moses than a priest, a temple official, or the very lawyer who initiated this whole smarty-pants discourse in the first place.

This interpretation suggests that the parable is an indictment of “othering,” the temptation and the act of treating a person as fundamentally different from us, whoever “we” are: as alien, separate, unclean, unworthy; as “illegal,” “thug,” “crazy,” “junky.”

I think this interpretation is true *and* that this essential message applies to the other important character in the story, the man on the side of the road. In fact, the Samaritan’s behavior only seems superhuman if we accept the premise of the chasm between the helper and helped.

If we take to heart the idea that the Samaritan truly sees the other traveler as a neighbor—not a stranger—some of the moral awe we feel goes away, right?

Imagine coming upon an important neighbor in your life on the road, half-dead. Of course you’d offer Good-Samaritan-level assistance, and then some. You wouldn’t even think about it. And you’d probably call some other neighbors to help as well, just as the Samaritan does.

**

It seems to me that “Go and do likewise” here becomes Good News if we take it not as an order to change the world one heroic individual act at a time, but as an invitation to change ourselves.

Think of the many ways you’ve helped or been helped by neighbors in your life, the favors and mercies, sure, but also the easy afternoons spent shooting the breeze about nothing in particular, perhaps with a cold beverage around a grill.

You’ve probably never tried to fix or save your neighbor. And to the extent that you’ve helped them, it’s probably been as much about your willing and companionable presence as any particular skill or largesse.

Can we learn to come to every new encounter in our lives with this kind of non-defensive, interested, community-minded stance? Can we replace our savior complex with a neighbor complex?

Of course, asking people’s names, talking about the weather, and sharing the proverbial cup of sugar will not save or fix any neighbor. Neither, by themselves, will these kinds of actions make a dent in the urgent, systemic moral crises of our day: 10,000 neighbors homeless in San Francisco, immigrants abused at the border and terrified in their homes, carbon being dumped into the atmosphere at a once-again accelerating rate.

But I truly believe, and I think Jesus does too, that as we learn to see and treat all people as if they were our neighbors—and allow them to see us that way too—world-changing action becomes not just possible, but natural and immediate. It becomes the collective work of a global spiritual neighborhood.