A Sermon for the Second Sunday of Lent:

Genesis 17:1-7, 15-16; Psalm 22:22-30; Romans 4:13-25; Mark 8:31-38

**

“O God, whose glory it is always to have mercy …” That’s how our Collect of the Day for this second Sunday of Lent begins.

It’s probably characteristic of our … indirect church communication style that such a profound insight into the Christian faith is shoved into a dependent clause—a clause from a prayer that I, at least, frequently fail to pay any attention to.

But perhaps that’s the charm and power of sticking our best theology in as asides in the sacred syntax: it allows us to be surprised in the Spirit when we do stumble across those insights.

That’s what happened to me when I read those words: “O God, whose glory it is always to have mercy.” I was surprised because glory and mercy are two words we use often in church, but seldom together.

Let’s spend a few minutes thinking about what that might mean.

When I hear the word “glory,” I think immediately of something like “fame and glory,” the glory of renown, of possessing admirable and perhaps enviable fortunes. Plenty of God’s servants possess this kind of glory in our religious tradition, especially the great kings David and Solomon.

Of course, the Bible also speaks to the spiritual danger of such glory: the temptation to forget that we can possess it only partially, and that it doesn’t make us above the law. We learn, sometimes the hard way, that whatever glory we may come into should ultimately be ascribed to God, the source of all good gifts.

The kings of Israel lost touch with that important truth, to their own detriment and, we are told, that of their nation as well.

So there’s a second, related sense of glory for us to consider: God’s own glory, to which the treasures of Solomon and our modern-day cathedrals and basilicas are meant merely to point.

Indeed, the image of God being worshiped for all eternity in the heavenly temple by choirs of angels and the communion of saints—that’s the ultimate expression of this idea. We need “sounding trumpets’ melodies” to wrap our hearts around this idea of glory, plus the best poetry we can muster.

**

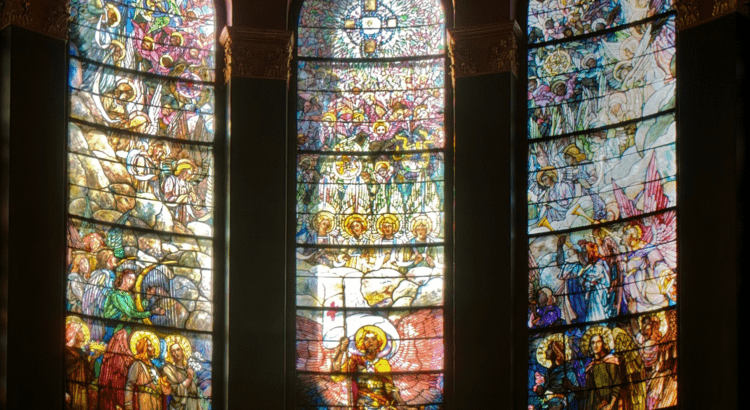

Or, perhaps you prefer a visual aid. If so, have a look at our “Victory in Heaven” window [in the nave / behind me], which depicts a similarly glorious scene after St. Michael and his forces have defeated the great enemy.

A few details always jump out at me. There are the requisite trumpets over on the right, of course. Gotta have trumpets to signal glory.

Simultaneously funny and quite poignant are what I take to be the cherubim in the upper portions of the central panels. Sure, the close ones look like little baby heads with wings. And that’s a little distracting.

But as our gaze moves from the nearby ones to the distant, I think we get the artists’ full effect. They seem to be a literal “throng” of angels—wings on wings on wings all the way up to the blazing cross of glory which I take to be symbolic of God’s very Being.

Indeed, it’s as if the ranks of God’s attendants are both countless and unwilling to settle for anything but the closest-packed position near their Creator. To be in God’s glorious presence is to be caught up in a truly irresistible grace.

That’s my interpretation of this scene anyway.

What’s pretty inarguable is that the image is a feast for the senses. And that’s the rub. Remember, it’s Lent, so it feels a little strange to be feasting.

While I do not think Lent is meant to be dour or joyless, I’ll admit that, at first blush, glory in the sense we’ve been exploring seems like a strange theme to focus on right now.

**

Mercy, on the other hand, is never far from our thoughts this time of year. We heard of it in Genesis and Romans this morning.

Though Sarah’s womb was barren and Abraham’s body “already good as dead,” these two great ancestors nevertheless “hop[ed] against hope” for the mercy of God’s deliverance. And God, in turn, promises them bounty beyond their wildest dreams.

Part of Paul’s point in our reading from Romans is that Abraham and Sarah’s story is our story too. By God’s mercy, we Christians can claim an inheritance in the promises of covenant loyalty. Of each of us, then, can it be said, “Once you were not a people, but now you are God’s people; once you had not received mercy, but now you have received mercy.

Of course, the mercy we receive from our Lord is wider by far than just this sense of deliverance from need and despair. Probably the aspect of God’s mercy that is most with us in this season is mercy as regards our guilt from “dust and sin.”

And more often than not, we reflect on our sinful state in a minor key. The emotional tone of our reflection is the humility of a “troubled spirit” and a “broken and contrite heart.” Perhaps the more subdued palate of the “I was thirsty …” window is more seasonally suitable: deep greens and blues, purples and reds. No vibrant pastels here.

**

That tone certainly puts us in a more appropriate headspace for processing this morning’s story from Mark’s gospel. Just before our passage from today, we hear Peter’s confession that Jesus is the Messiah. And so the curtain falls on Mark’s Act I, because finally even the thick-skulled disciples get it. Jesus is the Christ, the promised savior. Glorious indeed.

When the curtain comes up today, though, we first hear this: “Then he began to teach them that the Son of Man must undergo great suffering, and be rejected by the elders, the chief priests, and the scribes, and be killed, and after three days rise again.”

It’s simply not in Jesus’s vocation to hang around reveling in the glory of messiahship. Once the disciples understand that he is the Christ, immediately he strikes out toward Jerusalem on his final journey, his great errand of mercy.

In case we don’t get the point, the gospel writer says practically the same thing again in the next chapter in the story of the transfiguration, again through Peter. Beholding the dazzling spectacle, he says, “Rabbi, it is good for us to be here; let us make three dwellings.”

No, Jesus says, it is not yet time for me to reign in glory. Or, if you prefer, from today’s lesson: “Get behind me, Satan! For you are setting your mind not on divine things but on human things.”

Here’s the point: We can’t understand glory until we understand mercy. That’s what Jesus says to us again and again and again.

That’s a message we need to cling to as Christians, as New Yorkers, as Americans. It’s one I need to cling to as a straight white man with a passport, and a collar, and a retirement account, and a couple of graduate degrees. We can’t understand glory until we understand mercy.

I love trumpets and temples and the transfiguration, but I am also convinced that the glory of the Almighty and Everliving God cannot exist apart from the humility of the ever-merciful one who became obedient to the point of helplessness and death.

There’s a cross at the center of that glorious depiction of our Triune God. And so at the heart of Mark’s gospel lies the paradoxical truth that is at the heart of our faith: blessed are the merciful, exalted are the humble, worthy is the lamb.

Note: This is the first time I’ve based a Sunday sermon text on a previous version. It was fascinating to learn what feels “outdated” about how I wrote the last one and what doesn’t.