I read a paper in my cognition class a couple years back that kinda blew my mind.

In “How a Cockpit Remembers Its Speeds,” Edwin Hutchins makes the argument that a whole bunch of representational technology helps a flight crew “think” as a single system. The cognition in this system is socially shared and spatially distributed across the roles and procedures of pilot and copilot as well as the dials, displays, and other controls that they work with.

That’s an idea that would appeal, I think, to Bruno Latour, the theorist whose book Reassembling the Social* has more recently been rocking my world. Like Hutchins, Latour believes it’s silly to talk about human agency in a way that robs the objects we create, think with, and increasingly depend on of the significant part they play in our lives.

As a researcher studying religious meaning-making, I find these thinkers’ ways of looking at artifacts appealing. Bibles, icons, prayer beads, bread and wine—the role they play in our spiritual lives is really powerful and has the mark of a kind of presence that, like Latour, I don’t want to dismiss:

In addition to ‘determining’ and serving as a ‘backdrop for human action,’ things [i.e., objects] might authorize, allow, afford, encourage, permit, suggest, influence, block, render possible, forbid, and so on. (p. 71)

My ongoing dissertation study of a faith-adjacent nonprofit whose foster youth mentor teams gather each week in parks and coffee shops all around a large metropolitan area is helping me see this point even more clearly. Basketballs, Uno cards, and cute animals all play a part in this organization, as do the Instagram posts and newsletter reflections that tell the stories of how teams use these physical objects—and so many more—to practice and signify unconditional love.

Tapestry, as I call them, is changing a lot of lives, including mine. In my case, how could they not be, given how much of my time and energy is devoted to thinking and theorizing about them?

I’ve been spending some of that time and energy a little differently, lately. And that, dear reader, is why I have a recommendation for you, plus a technology hack that makes my new practice a little easier and cheaper.

**

I’m a pretty slow and undisciplined reader, which is a major liability when you’re working on a dissertation. I know I need to be reading more.

But I am a very attentive and agile listener: hence the pastoring, and also the podcasting.

Thus, it has totally revolutionized my reading and research life to get the hell away from my “desk,” i.e., wherever I’m sitting with my laptop checking my email too often, and learn by listening. (I’m just realizing that I’ve talked about this “lace up and listen” approach before).

I’ve been doing serious miles reading more while walking and running around the beautiful city of San Francisco, much of which I still haven’t explored (despite ample inspiration from the likes of a writer who’s walked every neighborhood*, plus delightful albeit fictitious characters like this programmer-turned-baker* and this designer-turned-decoder*). And since I’ve also started surfing, I now have added time for reading more on my once- or twice-weekly round trip to Pacifica (where these adorable surfers were back out in force on Saturday).

You probably know there are decent apps out there for reading PDFs aloud. These have been pretty helpful for me on this journey.

I ended up going with Voice Dream, which has good tools for keeping files organized. I also like that you can double tap on the text to move the “voice cursor” directly to a section where you want the narration to recommence. Unfortunately, it’s only available on iOS. Looks like NaturalReader, another pretty well rated one, is available for iOS and Android.

A tool I’d already been using for listening to long reads from online publications is Pocket, which as a bonus is now owned by Internet do-gooders Mozilla. Pocket’s a great tool even if you don’t have this eccentric desire to have someone else read to you.

Here’s the trouble: in my field, I need to be reading more actual books. I read almost exclusively on Kindle, though I’ve been delighted to discover the occasional book I need available as an audiobook. (I recommended the excellent audiobook of For White Folks Who Teach In The Hood* a couple newsletters ago.)

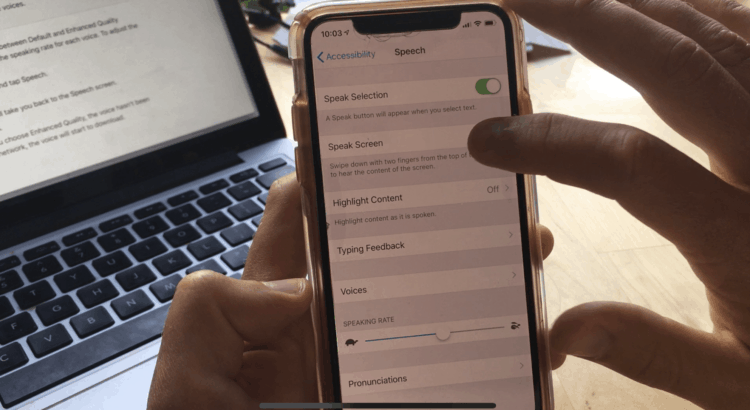

The problem is, audiobooks are rare in both academia and in mainline protestant religious publishing, plus when they do exist they’re understandably expensive—good audio is hard to make. So to really get the most out of learning by listening, I finally had to figure out how to get my iPhone’s accessibility features to read from me directly from the Kindle app.

It is not a super pleasant experience, as I suspect anyone who reads with a screen reader surely knows. I’m sure some of this also has to do with Amazon not wanting to discourage us from buying content on Audible.

(If you create online content, I hope this post will double as a call to attend to your content’s accessibility features.)

In any event, it is indeed possible to get your Kindle to read books to you. And it is possible to get used to the experience, even if the book you’re reading is full of pull quotes (as in Dear Church*), tables (as in Discourse Analysis Beyond the Speech Event*), and citations/footnotes (as especially in the writing of my new BFF, Latour). I know I’m dropping a lot of book links here, but I’m reading more than I have since seminary, y’all!

Let me walk you through it:

(Here’s a similar demo someone else made for Android.)

I’d love to hear from folks who find this possibility exciting, or who have similar reading/listening workflows. Perhaps I’m even weirder than usual in my willingness to slog through academic texts via robot voice and a finicky interface. Please don’t hesitate to tell me if you think that’s the case and I’ll just move the hell along.

What I know is that the need to be reading more books has been holding back my scholarship and probably my religious leadership for a long time. (For example, I listened to big chunks of Battered Love* preparing for my recent sermon on Hosea 1; I’m not sure I’d have read as much of it without this new technique.)

I also know that Hutchins and probably even Latour would probably believe me when I say that I think I’m remembering what I hear at least as well as what I read, especially when I’m walking around San Francisco. I can remember the neighborhood I was jogging in when I had a breakthrough in understanding Latour, the same neighborhood (though running in the other direction) as when I heard Renita Weems on the marriage metaphor in a way that went on to inform my sermon.

There’s something about mapping the books I’m reading onto the geography of the city that is helping me make connections I’m not sure I otherwise would have.

Plus it feels good to “read” with my whole body and not exclusively with my eyes and my note-taking fingers, especially as I continue to study religious organizations who stress getting out of their buildings and out into their neighborhoods.

* Disclosure: Affiliate links.